Welcome back to Cinema Obscura, where we dig up the weird, forgotten, and wonderfully strange corners of film history that most people never knew existed.

Key Takeaways

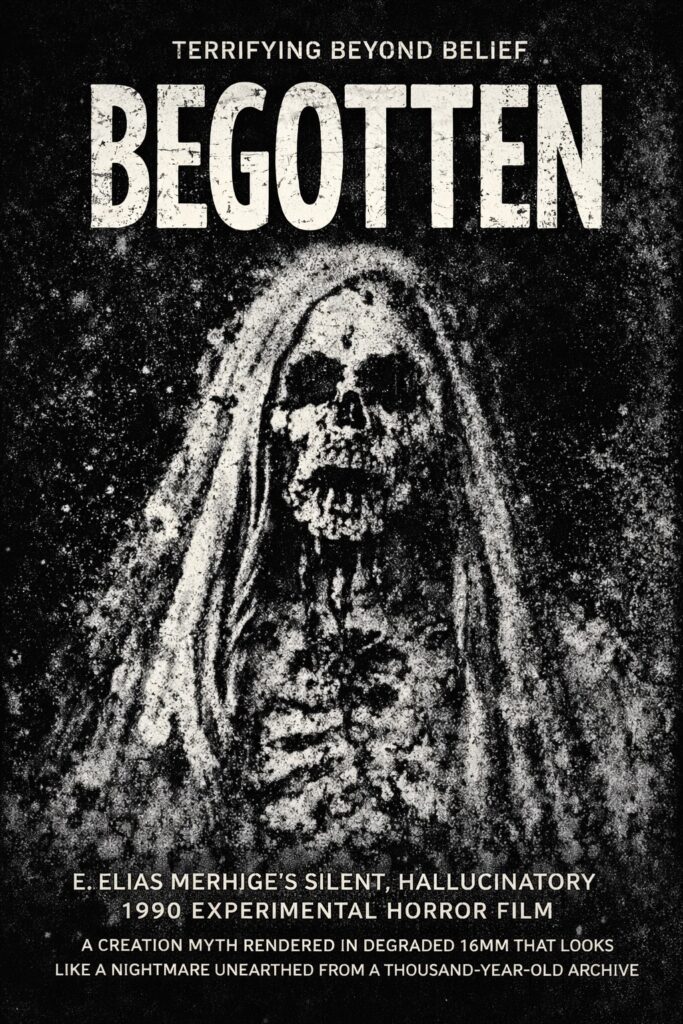

- Begotten is a 1990 American experimental horror film written, directed, and produced by E. Elias Merhige — a silent, dialogue-free creation myth rendered entirely in degraded black-and-white imagery.

- The film depicts a godlike figure disemboweling himself, the emergence of Mother Earth from his remains, and the birth and ritualistic destruction of their offspring — a retelling of Genesis as body horror.

- Merhige built his own optical printer from scratch and spent nearly ten hours of post-production work for every single minute of finished film, a process that consumed three years.

- Susan Sontag became the film’s unlikely champion, hosting private screenings in her apartment after discovering it through San Francisco film critics.

- Marilyn Manson played Begotten on a loop during the entire recording of his album Antichrist Superstar and later hired Merhige to direct music videos, while Nicolas Cage’s admiration for the film led directly to Merhige directing Shadow of the Vampire (2000).

The Film That Shouldn’t Exist

Some films are difficult. Some films are challenging. Begotten is something else entirely — a 72-minute assault on the visual cortex that looks less like a movie and more like a relic excavated from some pre-human civilization’s attempt to document the apocalypse.

There is no dialogue. There is no conventional narrative. There is no score in the traditional sense — only ambient drones, insect sounds, and the steady rhythm of a heartbeat buried beneath layers of noise. The imagery, processed through a laborious optical printing technique that stripped every frame down to pure black and pure white, renders even recognizable human bodies into throbbing, indecipherable shapes. Watching Begotten is less like watching a film and more like trying to decode a transmission from somewhere you were never meant to receive signals.

And yet it exists. A young theater director from New York made it, largely by himself, on 16mm reversal film, in locations scattered across New York City and New Jersey. He spent three years in post-production, alone with his homemade optical printer, re-photographing every frame until the images achieved a texture that looked ancient, corroded, and profoundly wrong.

The result is one of the most genuinely singular objects in the history of American cinema.

What Happens in the Film

To the extent that Begotten has a plot, it unfolds in three acts, each centered on a figure drawn from overlapping creation myths.

In the first, a robed figure sits in a dilapidated shack. Using a straight razor, he methodically disembowels himself. The credits identify him as “God Killing Himself.” He dies. From his remains, a woman emerges — Mother Earth. She brings the corpse to arousal, uses his seed to impregnate herself, and wanders into a barren landscape.

In the second act, Mother Earth gives birth to a fully grown but convulsing man — the Son of Earth — and abandons him in the wilderness. He twitches and shudders, unable to stand or speak, connected to the world only by an umbilical cord.

In the third, a group of faceless nomads discover the Son of Earth. They seize him. What follows is a prolonged ritual of brutality — the nomads drag him across the landscape, disembowel him, scatter his remains, and bury the pieces in the earth. Flowers grow from the soil where his body was planted.

That’s the film. What matters is not the sequence of events but the way Merhige renders them — so abstracted by the optical printing process that the viewer is constantly hovering between recognition and incomprehension, straining to decipher images that seem to resist being seen.

The Man Behind the Printer

Edmund Elias Merhige was born in 1964 and studied at the State University of New York at Purchase. He fell into experimental theater while in Manhattan, eventually founding a company called Theatreofmaterial, whose members would constitute most of Begotten‘s cast.

Merhige first conceived Begotten around 1984, when he was twenty years old. The original vision was ambitious — a multimedia dance-theater piece intended for Lincoln Center, with an estimated budget of $250,000. When it became clear that staging the production live was financially impossible, Merhige pivoted to film, beginning actual production in 1988.

The influences he brought to the project were wide-ranging and deliberately obscure: the transgressive theater theories of Antonin Artaud, the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, the experimental cinema of Stan Brakhage, the clinical horror of Georges Franju’s documentary Blood of the Beasts, and the expressionist nightmare logic of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. But the single most decisive influence was documentary footage of the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The degraded, nearly illegible quality of those images — the way the destruction had been captured on film stock that itself seemed to be dying — became the aesthetic template for Begotten.

The film was shot on location in New York City and New Jersey over five and a half months, using a 16mm Arriflex silent camera with black-and-white reversal film. The actors, drawn primarily from Theatreofmaterial, endured extended takes involving simulated gore made from corn syrup and animal byproducts. Merhige directed through improvisation, encouraging his performers to respond instinctively within ritualistic setups.

Ten Hours Per Minute

The post-production process is the stuff of genuine filmmaking legend.

After completing principal photography, Merhige spent eight months building an optical printer from scratch. An optical printer is essentially a device that re-photographs film one frame at a time, allowing the filmmaker to manipulate exposure, contrast, and focus at the most granular level possible. Using this homemade machine, Merhige re-processed every frame of Begotten, pushing the contrast to extremes until the image collapsed into areas of pure white and pure black, with almost nothing in between.

The process took approximately ten hours of labor to produce one minute of finished film. For a 72-minute movie, the math is staggering — roughly 720 hours of optical printing work, spread across a post-production period that lasted three years. Merhige has described the experience as ritualistic and transformative, saying that the act of making the film became inseparable from its subject matter — creation and destruction occurring simultaneously, frame by frame, in a darkened room.

The result is imagery that looks like no other film ever made. It evokes early silent cinema, war photography, medical documentation, and religious iconography all at once, without quite resembling any of them. The images throb and shimmer, as though the film stock itself is alive and in pain.

Susan Sontag’s Living Room

After completing Begotten, Merhige spent two years trying to find a distributor. The response was uniformly discouraging. One distributor told him that if he could show it for free in a high school basement in the Bronx, he’d be lucky.

The film’s earliest screening took place in October 1989 at the Goethe-Institut as part of the Montreal World Film Festival. Reports described a majority of the audience as too stunned by what they’d seen to react. It then played at the San Francisco International Film Festival in April 1990, where film critics Tom Luddy and Peter Scarlet took notice. Impressed by the film’s visual ambition, they brought it to the attention of Susan Sontag.

Sontag, one of the most influential cultural critics of the twentieth century, became Begotten‘s most improbable and most important advocate. She hosted private screenings in her apartment for critics and filmmakers, effectively building the film’s reputation through word of mouth at the highest levels of New York’s intellectual establishment. The film subsequently screened at the Museum of Modern Art, the Film Forum, the American Cinematheque, and the Ann Arbor Film Festival.

None of this translated into a theatrical release. Begotten never played in commercial cinemas. It existed instead as an underground phenomenon — passed around on bootleg VHS tapes, whispered about on early internet forums, and eventually uploaded to YouTube, where it found an entirely new audience of teenagers trawling “most disturbing movies” lists.

The Manson Connection

In the mid-1990s, Marilyn Manson discovered Begotten and became perhaps its most vocal celebrity admirer. According to multiple accounts, Manson played the film on a continuous loop during the entire recording of his 1996 album Antichrist Superstar. The album’s art designer, P.R. Brown, was instructed to watch the film while developing the cover artwork.

Manson subsequently contacted Merhige and hired him to direct music videos for two songs from the album. The video for “Cryptorchid” incorporated imagery drawn directly from Begotten, while the “Antichrist Superstar” video extended the film’s aesthetic into Manson’s performative universe. Merhige also contributed to the stage production for the album’s tour.

The Manson association did more to raise Begotten‘s profile than any amount of festival screenings ever could. It introduced the film to an audience of millions — albeit an audience that largely encountered it as an artifact of shock culture rather than as the work of experimental art cinema that Merhige intended.

Shadow of the Vampire and After

A decade after Begotten, Merhige directed Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a fictional account of the making of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu starring John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe. The film earned Dafoe an Academy Award nomination. Merhige got the job largely because Nicolas Cage, who co-produced, had seen and admired Begotten.

The leap from a dialogue-free experimental horror film made on a homemade optical printer to a studio production starring A-list actors is one of the stranger career trajectories in recent film history. Merhige went on to direct one more feature — the FBI thriller Suspect Zero (2004) with Aaron Eckhart and Ben Kingsley — before largely returning to theater work.

He did eventually return to the Begotten universe. Din of Celestial Birds (2006) and Polia & Blastema: A Cosmic Opera (2022) are both short film sequels that continue the mythological cycle Merhige began in the original film. Neither has achieved the same level of notoriety as the original, but their existence confirms that Begotten was never intended as a one-off provocation. It was the first chapter in a cosmology that Merhige has been building for over thirty years.

Why It Matters

Begotten is not an easy film to recommend. It is not entertaining in any conventional sense. Many viewers — including sympathetic ones — find it tedious, indecipherable, or simply gross. The Letterboxd reviews are telling: alongside passionate five-star defenses, you’ll find equally passionate accusations that the whole thing is an elaborate pretension, a student film with ambitions far exceeding its grasp.

But Begotten matters because it represents something genuinely rare in American cinema: an uncompromising artistic vision executed with monastic dedication and absolutely zero concern for commercial viability. Merhige spent years of his life alone in a room, re-photographing film one frame at a time, to create something that no distributor wanted and no audience was waiting for. The result looks like nothing else. It sounds like nothing else. It feels like nothing else.

Whether that constitutes genius or folly is genuinely up to you. But the fact that Begotten exists at all — that someone actually made this thing, by hand, in a New York apartment — is itself a kind of miracle. Or possibly a kind of curse. The film wouldn’t have it any other way.

Quick Facts

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Title | Begotten |

| Year | 1990 (completed 1989) |

| Runtime | 72 minutes |

| Director | E. Elias Merhige |

| Screenplay | E. Elias Merhige |

| Cinematography | E. Elias Merhige |

| Format | 16mm black-and-white reversal film |

| Cast | Brian Salzberg, Donna Dempsey, Stephen Charles Barry, Theatreofmaterial |

| Country | USA |

| Distributor | World Artist Home Video (VHS) |

| Budget | Undisclosed (micro-budget) |

| Notable Screenings | Montreal World Film Festival, San Francisco International Film Festival, MoMA, Film Forum, Ann Arbor Film Festival |

| IMDb Rating | 5.5/10 |

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Begotten About?

The film is a silent, dialogue-free retelling of creation mythology. It depicts a godlike figure who kills himself, the emergence of Mother Earth from his remains, her self-impregnation, the birth of the Son of Earth, and his ritualistic destruction by faceless nomads. The narrative draws on Christian, Celtic, and Slavic pagan creation myths.

Is Begotten a Horror Film?

It occupies a space between experimental art cinema and horror. It contains extremely graphic imagery — including extended scenes of self-disembowelment — but presents them in such an abstracted, degraded visual style that they function more as ritualistic tableaux than conventional horror set pieces. Whether it frightens you or bores you depends almost entirely on your tolerance for non-narrative cinema.

How Was the Film’s Visual Style Created?

Merhige built an optical printer from scratch and used it to re-photograph every frame of the 16mm footage, pushing the contrast to extreme levels until only pure black and pure white remained. This process took approximately ten hours per minute of finished film and consumed three years of post-production.

Did Begotten Get a Theatrical Release?

No. Despite screenings at major film festivals and art institutions — including MoMA and Film Forum — the film never secured commercial distribution. It circulated primarily through bootleg VHS tapes and, later, unauthorized YouTube uploads. A limited VHS release from World Artist Home Video is the closest it came to official home video distribution.

What Is the Connection to Marilyn Manson?

Manson played Begotten on a loop during the recording of Antichrist Superstar (1996) and subsequently hired Merhige to direct music videos for the album. The partnership introduced the film to a much wider audience, though primarily as an object of shock culture rather than as experimental cinema.

What Did Merhige Do After Begotten?

Merhige directed Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a critically acclaimed fictional account of the making of Nosferatu that earned Willem Dafoe an Oscar nomination. He followed this with Suspect Zero (2004) before returning primarily to theater work. He has made two short film sequels to Begotten: Din of Celestial Birds (2006) and Polia & Blastema: A Cosmic Opera (2022).

Cinema Obscura is a recurring series on Choking on Popcorn where we explore the strangest, most forgotten, and most fascinating films that most people have never heard of. Got a suggestion for a future entry? Contact us.