Welcome back to Cinema Obscura, where we dig up the weird, forgotten, and wonderfully strange corners of film history that most people never knew existed.

Key Takeaways

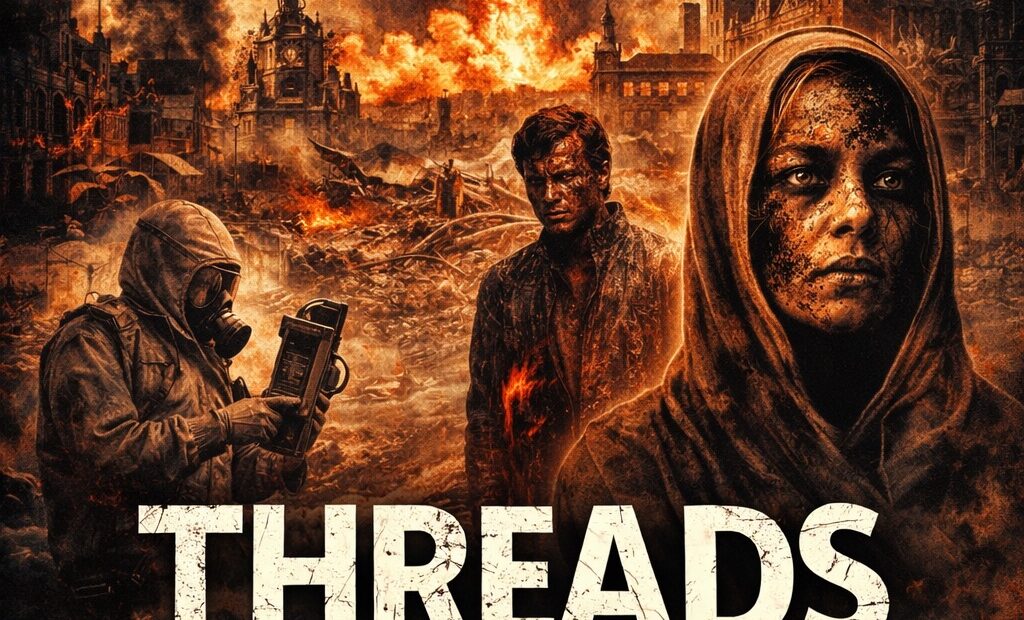

- Threads is a 1984 BBC television film depicting the effects of a nuclear attack on Sheffield, England, directed by Mick Jackson and written by Barry Hines (author of Kes).

- The film follows two working-class families from ordinary domestic life through nuclear annihilation and the decades of societal collapse that follow.

- Its original broadcast on September 23, 1984, drew 6.9 million viewers and became known in broadcasting circles as “the night the country didn’t sleep.”

- The film was meticulously researched using Carl Sagan’s nuclear winter papers, government contingency plans, and survivor accounts from Hiroshima.

- It was the first dramatization to depict a nuclear winter, and has experienced a major resurgence in popularity in recent years.

The Night Britain Couldn’t Sleep

At 9:30 PM on September 23, 1984, the BBC broadcast a television film. When it ended, millions of viewers turned off their sets and sat in silence. Many couldn’t bring themselves to go to bed. Some reported nightmares for weeks. The date became known in British broadcasting circles by a single phrase: “the night the country didn’t sleep.”

The film was Threads. And forty years later, it remains quite possibly the most upsetting thing ever shown on television.

This isn’t hyperbole. Threads isn’t a horror film in any conventional sense — there are no monsters, no supernatural elements, no jump scares. What it offers instead is something far worse: a meticulously researched, clinically detailed depiction of what would actually happen to ordinary people in an ordinary British city if nuclear weapons were used. Not the sanitized Hollywood version. Not the heroic post-apocalyptic rebuild. The real thing, as far as science and government planning documents could project it, presented with a documentary’s commitment to accuracy and a dramatist’s instinct for maximum emotional devastation.

The Setup

The first 46 minutes of Threads are almost deceptively normal. We meet two Sheffield families — the Kemps and the Becketts — connected by a young couple, Jimmy Kemp and Ruth Beckett, who discover Ruth is pregnant. Their lives are ordinary in the most deliberately mundane sense: tea is made, arguments are had about wedding plans, parents fuss over money.

Meanwhile, in the background — literally in the background, on televisions and radios that nobody is quite paying attention to — the geopolitical situation between the United States and the Soviet Union deteriorates. News bulletins about a confrontation in Iran grow more frequent and more urgent. Most of the characters barely notice. They have lives to get on with.

This is the film’s first and most devastating trick. By grounding us so thoroughly in kitchen-sink domestic reality, writer Barry Hines and director Mick Jackson ensure that when the bombs fall, we aren’t watching anonymous victims. We’re watching people whose laundry we’ve seen hanging on the line.

The Research

Director Mick Jackson didn’t approach Threads as a creative exercise. He approached it as a scientific one. Before cameras rolled, he consulted an extraordinary range of sources. Carl Sagan’s 1983 paper on nuclear winter provided the atmospheric modeling. Duncan Campbell’s 1982 exposé War Plan UK revealed the British government’s actual (and alarmingly inadequate) contingency plans. Magnus Clarke’s 1982 book Nuclear Destruction of Britain supplied the psychological projections. The behavioral research drew heavily on accounts from Hiroshima’s survivors, the Hibakusha.

Sheffield was chosen as the setting partly because its city council had declared it a “nuclear-free zone,” making local government sympathetic to the production, and partly because it represented a plausible Soviet military target — an industrial city in the center of the country with nearby military installations.

Auditions were advertised in Sheffield’s The Star newspaper, and held in the ballroom of Sheffield City Hall. Eleven hundred people showed up. Extras were selected based on height and age and told to wear ragged clothes and look “miserable.” The majority were Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament supporters. The makeup for third-degree burn victims consisted of Rice Krispies and tomato ketchup. A prop umbilical cord was fashioned from liquorice.

The budget was £400,000. The ambition was to change how an entire country thought about nuclear war.

The Attack

Forty-six minutes in, the sirens sound.

What follows is presented with a documentarian’s precision and a filmmaker’s understanding of how images lodge in the brain. Milk bottles melt on doorsteps. A woman standing in the street urinates herself as a mushroom cloud rises on the horizon — the actress Anne Sellors received a screen credit simply reading “Woman Who Urinates Herself,” which has become one of the most cited details in the film’s legend. Tower blocks collapse. The soundtrack drops to silence, then wind, then the crackle of burning.

And then it gets worse. Because the genius of Threads — if “genius” is the right word for something this harrowing — is that the nuclear attack itself occupies only a few minutes of screen time. The remaining hour follows the aftermath: weeks, months, years, and ultimately over a decade of unrelenting societal collapse.

There is no food distribution. No medical care. No communications. Typhoid and dysentery run rampant. Radiation sickness claims those the blast spared. Nuclear winter descends. The government’s bunker-bound officials, who spent the first half of the film running drills with a confidence that now seems pathological, are revealed as utterly impotent. Ruth gives birth alone in a barn, biting through the liquorice umbilical cord herself, not knowing what the radiation has done to her child.

What Makes It Different

The nuclear apocalypse has been dramatized many times — in The Day After (1983), Testament (1983), When the Wind Blows (1986), and dozens of others. What separates Threads from all of them is its refusal to offer even a molecule of hope.

There are no heroic survivors banding together. No love stories blooming in the wreckage. No tentative signs of rebuilding. The film’s final act, set thirteen years after the attack, depicts a generation of children who have grown up without education, without language beyond grunted fragments, without any connection to the civilization that preceded them. The “threads” of the title — the social, cultural, and institutional connections that hold a society together — have been severed permanently.

Barry Hines, who also wrote the novel that became the beloved film Kes, understood working-class British life with a specificity that gives the domestic scenes their devastating texture. And Mick Jackson, who had previously produced the BBC documentary A Guide to Armageddon in 1982, knew exactly how to bridge the gap between scientific accuracy and emotional impact.

The result is a film that makes most post-apocalyptic fiction look like wish fulfillment.

The Aftermath (of the Broadcast)

The response was immediate and visceral. Labour leader Neil Kinnock wrote to Jackson the morning after broadcast, declaring that “the story must be told time and time again until the idea of using nuclear weapons is pushed into past history.” He added: “Don’t be troubled by the possibility that some people might be inured to the Real Thing by seeing horrifying films. The dangers of complacency are much greater than any risks of knowledge.”

U.S. Secretary of State George Shultz reportedly watched the film when it aired on CNN in 1985, and it has been alleged that it influenced the Reagan administration’s evolving attitude toward nuclear war. The film was broadcast again on BBC1 in 1985 and then, remarkably, disappeared from British television screens for nearly two decades.

Jackson himself has spoken about the psychological toll of making the film. In a 2024 interview marking its 40th anniversary, he described still suffering from a form of PTSD related to the production — the process of visualizing nuclear annihilation in such detail and holding those images in his head while directing proved to be personally devastating.

He went on to have a successful Hollywood career — he directed The Bodyguard (1992) and Denial (2016), among others — but nothing he made before or after carried the same cultural weight as those 112 minutes of BBC television.

The Resurgence

After years of near-invisibility, Threads has experienced a remarkable revival. Severin Films released a restored Blu-ray in the United States in 2018. A mass rewatch organized on social media under the hashtag #ThreadDread drew widespread participation. The film now holds a 100% critics’ score on Rotten Tomatoes — the Apple TV listing and various streaming platforms have made it accessible to a new generation.

The timing is grimly appropriate. With the Doomsday Clock at 90 seconds to midnight — closer than it has ever been — Threads feels less like a historical artifact and more like a warning that remains stubbornly relevant.

In 2018, an American teenager wrote to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, imploring filmmakers to create a new terrifying nuclear war film for her generation. She may not have needed one. The 1984 original still does the job.

Should You Watch It?

This requires a genuine content warning. Threads is not entertainment in any conventional sense. It is an endurance test designed with surgical precision to leave you shaken. Viewers regularly describe it as one of the most disturbing viewing experiences of their lives — more upsetting than any horror film, more emotionally devastating than most prestige dramas.

If you’re someone who thinks the nuclear threat is abstract, distant, or theoretical, Threads exists to disabuse you of that notion with extreme prejudice. If you’re already anxious about geopolitical tensions, approach with serious caution.

But as a piece of filmmaking — as a demonstration of what television drama can do when it commits fully to confronting its audience with uncomfortable reality — Threads is without peer. It is the definitive dramatization of nuclear war, and it earns that status not through spectacle but through an almost unbearable accumulation of mundane, specific, scientifically grounded detail.

It is 112 minutes long. You will not enjoy them. You will never forget them.

Quick Facts

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Title | Threads |

| Year | 1984 |

| Runtime | 112 minutes |

| Director | Mick Jackson |

| Writer | Barry Hines |

| Lead Cast | Karen Meagher, Reece Dinsdale |

| Country | UK / Australia |

| Production | BBC, Nine Network, Western-World Television |

| Budget | £400,000 |

| First Broadcast | September 23, 1984, BBC Two |

| Viewership | 6.9 million (highest BBC Two rating that week) |

| Rotten Tomatoes | 100% (critics) |

| IMDb Rating | 7.9/10 |

| Home Video | Severin Films (Blu-ray, 2018); Simply Media (DVD, 2018) |

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Threads Based on Real Government Plans?

Yes. Writer Barry Hines and director Mick Jackson consulted real British government contingency plans, scientific papers on nuclear winter (including Carl Sagan’s work), and survivor accounts from Hiroshima. The film’s depiction of inadequate local government bunkers and failed civil defense reflects actual UK planning at the time.

How Does Threads Compare to The Day After?

Both were produced around the same time and deal with nuclear war’s effects on ordinary people. However, The Day After is an American network television production with recognizable actors, a larger budget, and a somewhat softer landing. Threads is widely considered the more uncompromising and scientifically rigorous of the two, particularly in its depiction of long-term societal breakdown.

Why Was the Film Barely Shown After 1985?

After airing twice (1984 on BBC Two, 1985 on BBC One), the film essentially disappeared from British television until a 2003 screening. The reasons have never been officially explained, though the film’s extreme emotional impact and the shifting geopolitical landscape after the Cold War may have contributed.

Where Can I Watch Threads?

The film is available on physical media through Severin Films (US Blu-ray) and Simply Media (UK DVD). It’s also available for streaming or digital rental through various platforms, including Apple TV. It has also been freely available on YouTube at various times.

Is There Going to Be a Remake?

As of the film’s 40th anniversary in 2024, discussions about a remake have been reported, but nothing has been confirmed. Director Mick Jackson and actor Reece Dinsdale have both commented publicly on the possibility.

Cinema Obscura is a recurring series on Choking on Popcorn where we explore the strangest, most forgotten, and most fascinating films that most people have never heard of. Got a suggestion for a future entry? Contact us.