Welcome back to Cinema Obscura, where we dig up the weird, forgotten, and wonderfully strange corners of film history that most people never knew existed.

Key Takeaways

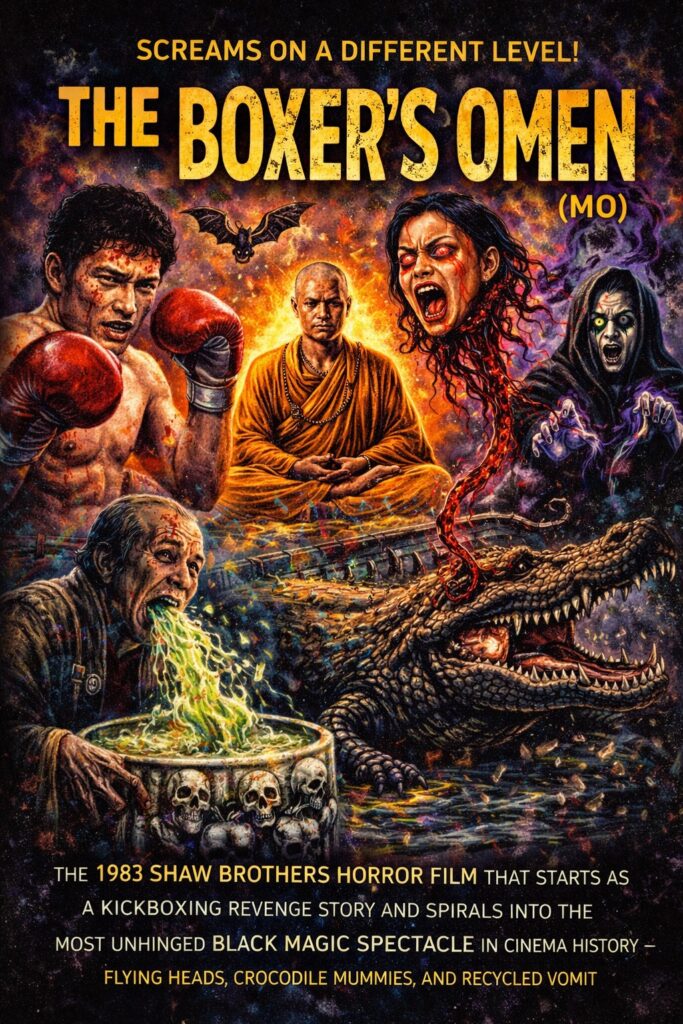

- The Boxer’s Omen (Chinese title: 魔, “Mo,” meaning “Magic”) is a 1983 Hong Kong horror film directed by Kuei Chih-Hung and produced by the legendary Shaw Brothers Studio.

- What begins as a straightforward kickboxing revenge film (featuring Bolo Yeung of Enter the Dragon fame) pivots into a hallucinatory supernatural epic involving Buddhist monks, black magic duels, reincarnation, and some of the most grotesque practical effects ever committed to celluloid.

- The film was part of Shaw Brothers’ desperate late-period attempt to compete with Hong Kong’s emerging “New Wave” filmmakers by pushing exploitation content to extremes.

- It was virtually unseen in the West until Image Entertainment’s 2006 DVD release, and has since been included in Arrow Video’s Shawscope: Volume 2 Blu-ray box set.

- Director Kuei Chih-Hung retired from filmmaking in 1984, emigrated to the United States, and opened a pizza parlor — one of cinema history’s most dramatic career pivots.

You Are Not Prepared

Every film review of The Boxer’s Omen begins with some version of the same disclaimer: nothing anyone writes about this film can adequately prepare you for the experience of watching it. This is not critical hyperbole. This is a public service announcement.

The film contains, in no particular order: a man vomiting a live moray eel in a hotel room; a nude woman birthed from the sewn-shut corpse of a crocodile; a wizard who tears his own head off his body and attacks his enemy with the dangling spinal cord; armies of animated alligator skulls chomping across a fog-shrouded set; flocks of blood-sucking bat puppets; a ritual involving the consumption of regurgitated chicken parts; spider-stingers that bore through a monk’s eyeballs; a levitating demon head bathed in neon green light; and extended scenes of characters eating each other’s vomit as part of black magic ceremonies.

And this is a film produced by the same studio that made 36th Chamber of Shaolin and Come Drink with Me.

Welcome to the deep end of Shaw Brothers.

The Plot (Insofar as One Exists)

The film opens with something recognizable: a boxing match. Chan Wing, a Hong Kong heavyweight, fights the Thai champion Bu Bo (played by Bolo Yeung, the mountain of muscle who fought Bruce Lee in Enter the Dragon). Wing wins the match, but Bu Bo lands a vicious sucker punch after the bell, paralyzing Wing from the waist down.

Wing’s brother, Chan Hung (Philip Ko Fai), is a Hong Kong gangster who vows revenge. He travels to Thailand to challenge Bu Bo to a rematch. So far, so standard — this is the kind of setup that Shaw Brothers had been cranking out for two decades.

Then Chan Hung vomits an eel, and the film leaves planet Earth.

Hung begins seeing visions of a Buddhist monk. He visits a Thai temple, where the monks explain that their recently deceased head abbot, Qing, was Hung’s twin brother in a past life. Qing was on the verge of achieving immortality when a black magic wizard assassinated him by training spiders to stab him through the eyes. Qing’s soul is now trapped in his decaying body, and only Hung — by becoming a monk himself, defeating the black magicians, and completing certain rituals — can help Qing achieve transcendence.

Hung shaves his head, takes the monastic name Baluo Kaidi, trains in arduous conditions, receives magical powers, and enters a ritualistic duel with the wizard who killed Qing. The duel involves — and I cannot stress this enough — animated crocodile skulls, a levitating demon head, blood-sucking bats, and a wizard tearing off his own head and using his intestinal tract as a weapon.

Baluo wins. He returns to Hong Kong. He breaks his monastic vow of chastity by sleeping with his girlfriend. This triggers a magical backlash during his boxing match with Bu Bo, requiring a second journey to Thailand, a side trip to Nepal to retrieve sacred ashes, and a final confrontation with a coalition of black magicians that makes everything that came before look restrained.

Shaw Brothers in Decline

To understand how The Boxer’s Omen came to exist, you need to understand the state of Shaw Brothers Studio in the early 1980s.

Shaw Brothers had dominated Hong Kong cinema through the 1960s and 1970s, producing hundreds of martial arts films on their massive studio compound in Clearwater Bay. The formula was reliable: take a simple revenge or honor-based plot, cast it with athletic performers, shoot it on elaborate studio sets, and distribute it across Asia and into grindhouse theaters worldwide.

By the early 1980s, the formula was failing. A new generation of Hong Kong filmmakers — directors like Tsui Hark, Ann Hui, and John Woo — were producing faster, grittier, more contemporary work that made Shaw Brothers’ studio-bound productions feel creaky. The kung fu boom had cooled. Audiences wanted something different.

Shaw Brothers’ response was to push into exploitation territory — horror films, black magic films, and increasingly graphic content designed to compete on shock value rather than martial arts choreography. The studio had been experimenting with horror since 1975, when director Ho Meng-hua made Black Magic, a film about Thai folk sorcery that established the template: take a martial arts or crime plot, set it in Southeast Asia (exotic and vaguely threatening to Hong Kong audiences), and pile on supernatural horror sequences involving gross-out ingredients like bodily fluids and animal parts.

The Boxer’s Omen represents the absolute apex of this approach. It is a film where the restraint dial has been removed entirely, where every scene seems to be in competition with the previous scene for the title of Most Insane Thing Ever Filmed. The studio that built its reputation on choreographed fight sequences was now staging choreographed black magic duels where the weapons included regurgitated food and animated corpses.

It did not save the company. Shaw Brothers stopped producing feature films in 1986 and transitioned to television.

Kuei Chih-Hung: From Horror to Pizza

Director Kuei Chih-Hung had a résumé perfectly suited to the material. He had directed exploitation films across multiple genres for Shaw Brothers, including the Bruceploitation hit Iron Dragon Strikes Back, the creature feature Killer Snakes, and the women’s prison film Bamboo House of Dolls. His previous horror film Bewitched (1981), which explored similar Thai black magic territory, is sometimes considered a companion piece or predecessor to The Boxer’s Omen.

Kuei brought a workmanlike efficiency to the film’s production — the movie moves at a pace that barely allows you to process one outrageous image before the next one arrives — and a genuine flair for the supernatural set pieces. The ritual duel sequences are staged with a wild creativity that belies their low budgets. The neon-lit sets, the Day-Glo color schemes, and the relentlessly inventive practical effects create a visual experience that critics have compared to Jodorowsky, early Peter Jackson, and a particularly aggressive acid trip.

The Boxer’s Omen was the second-to-last film of Kuei’s career. After directing one more Shaw Brothers production in 1984, he retired from filmmaking, emigrated to the United States, and opened a pizza parlor. It is, as cinema career pivots go, perhaps the most dramatic in the history of the medium. One year he was directing a film in which a wizard tears his own head off and strangles a monk with his dangling entrails. The next year he was making pepperoni.

The Effects

The practical effects in The Boxer’s Omen deserve their own discussion, not because they are technically accomplished — many of them are cheerfully crude — but because they are relentlessly inventive and committed to their own internal logic. Every black magic sequence follows an elaborate procedural structure: ingredients must be gathered, rituals must be performed in specific order, and counter-spells have specific rules and limitations.

Gordon Chan, who would later become a successful Hong Kong director in his own right, was a member of the special effects unit on the film. The effects combine puppetry, optical compositing, stop-motion animation, prosthetic makeup, and large quantities of what appears to be slime, gore, and various food products pressed into service as supernatural substances.

The standout sequence — and the one most frequently cited in reviews — involves the resurrection of a corpse from inside a crocodile. The ritual requires an actual crocodile to be cut open on camera (the film, it should be noted, was made in an era with essentially no animal welfare oversight in Hong Kong film production), and a body to be placed inside and sewn shut. The resulting “birth” — a nude woman emerging from the crocodile corpse, covered in maggots that buzz like insects — is simultaneously revolting, hypnotic, and completely unique in cinema history.

Discovery and Cult Status

For over two decades, The Boxer’s Omen was essentially invisible in the West. It circulated among dedicated collectors of Hong Kong exploitation cinema, but had no official English-language home video release until Image Entertainment put it out on DVD in November 2006.

The DVD arrived into a world primed to receive it. The internet had created communities of cult film enthusiasts who had been exchanging whispered recommendations about Shaw Brothers’ most extreme output. The DVD — featuring a surprisingly clean print, a booklet by horror writer Stephen Gladwin, and a collection of vintage Asian B-movie trailers — became an instant object of fascination.

In December 2022, Arrow Video included the film in their massive Shawscope: Volume 2 Blu-ray box set, giving it the kind of lavish, cinephile-approved treatment that would have been unthinkable when Kuei was making the film. The set includes fourteen Shaw Brothers films and extensive supplementary materials, allowing The Boxer’s Omen to take its place alongside the studio’s more “respectable” martial arts output.

The film was also selected for screening at the 2011 Maryland Film Festival, where the presenting sponsor was — in one of those perfect cultural collisions — the band Animal Collective.

Why It Matters

The Boxer’s Omen is not a “good” film in any conventional critical sense. Its narrative is incoherent, its performances are functional at best, and its tonal register operates in a register somewhere beyond human comprehension. But it is an extraordinary film — a document of a specific moment in Hong Kong cinema when a desperate studio threw every idea it could think of at the screen and produced something that, forty years later, remains genuinely shocking, genuinely creative, and genuinely unlike anything else.

It matters because it represents a tradition of popular cinema — Southeast Asian supernatural horror, with its folk magic rituals, its Buddhist and animist cosmology, and its cheerful willingness to show you things you’ve never seen and never wanted to see — that rarely makes it into Western film discourse. For audiences raised on Hollywood horror, The Boxer’s Omen is a reminder that the genre has always been global, always been weirder than you think, and always been willing to go further than you’re comfortable with.

It also has a man tearing his own head off and strangling someone with his spinal cord. If that’s not Cinema Obscura material, nothing is.

Quick Facts

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Title | The Boxer’s Omen (魔 / Mo) |

| Year | 1983 |

| Runtime | 107 minutes |

| Director | Kuei Chih-Hung |

| Screenplay | On Szeto (I On-Leung) |

| Stars | Philip Ko Fai, Elvis Tsui, Bolo Yeung |

| Country | Hong Kong |

| Studio | Shaw Brothers |

| Distributor | Image Entertainment (2006 DVD), Arrow Video (2022 Blu-ray) |

| Budget | Undisclosed (high by Shaw Brothers standards) |

| IMDb Rating | 7.0/10 |

| Related Films | Bewitched (1981), Black Magic (1975), Seeding of a Ghost (1983) |

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is The Boxer’s Omen About?

A Hong Kong gangster travels to Thailand to avenge his brother, who was paralyzed by a cheating Thai boxer. While there, he discovers he’s the reincarnated twin of a deceased Buddhist monk and must become a monk himself to defeat a cabal of black magic wizards. The film is about 25% kickboxing and 75% supernatural insanity.

Is This Really a Shaw Brothers Film?

Yes. Shaw Brothers Studio, best known for classics like The 36th Chamber of Shaolin and Five Deadly Venoms, produced The Boxer’s Omen as part of their early-1980s push into horror and exploitation content. It represents the extreme end of the studio’s output.

How Gross Is It?

Very. The film includes scenes of characters consuming regurgitated food, extended sequences involving animal viscera, a corpse being placed inside a real crocodile, and various other images that are difficult to describe in a family-friendly context. If you have a weak stomach, this is not your film.

What Happened to the Director?

Kuei Chih-Hung retired from filmmaking in 1984, one year after The Boxer’s Omen, and emigrated to the United States, where he opened a pizza restaurant. He never returned to directing.

Where Can I Watch It?

The film is available on Blu-ray as part of Arrow Video’s Shawscope: Volume 2 box set (released December 2022), which includes thirteen other Shaw Brothers films. The earlier Image Entertainment DVD from 2006 is out of print but may be available secondhand. It also screens occasionally at repertory cinemas and film festivals.

Is This Connected to Other Shaw Brothers Horror Films?

Yes. The Boxer’s Omen is sometimes considered a sequel to Bewitched (1981), also directed by Kuei Chih-Hung and exploring similar Thai black magic themes. Both films are part of a broader Shaw Brothers subgenre of “black magic films” that began with Black Magic (1975). Other related titles include Seeding of a Ghost (1983) and Hex (1980).

Cinema Obscura is a recurring series on Choking on Popcorn where we explore the strangest, most forgotten, and most fascinating films that most people have never heard of. Got a suggestion for a future entry? Contact us.