Welcome back to Cinema Obscura, where we dig up the weird, forgotten, and wonderfully strange corners of film history that most people never knew existed.

Key Takeaways

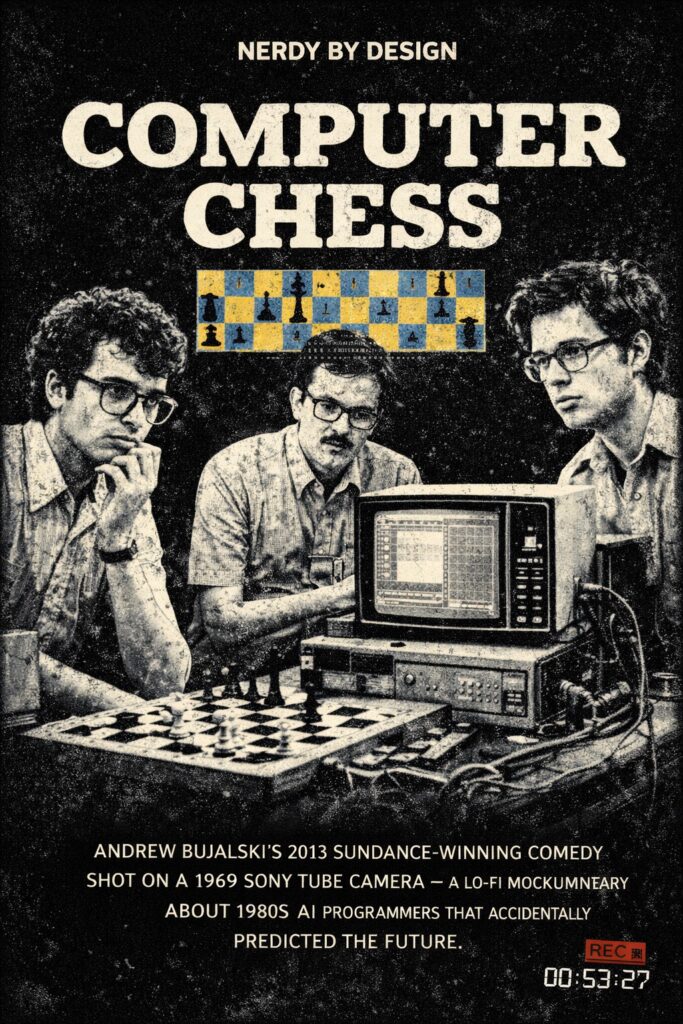

- Computer Chess is a 2013 American independent comedy-drama directed by Andrew Bujalski, set at a fictional early-1980s computer chess tournament and shot entirely on vintage 1969 Sony AVC-3260 analog tube cameras.

- The film was made from an eight-page treatment rather than a conventional screenplay, with largely improvised dialogue from a cast of non-professional actors who actually understood computer science.

- It won the Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and holds an 88% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

- The film’s questions about artificial consciousness, machine learning, and the relationship between humans and computers proved remarkably prescient — released a full decade before the AI explosion of 2023.

- The entire production cost approximately $78,000, partially funded through crowdfunding and a $43,500 grant from USA Artists.

A Film from a Camera from 1969

The first thing you notice about Computer Chess is that it looks wrong. Not stylistically wrong in the way that a desaturated thriller or an over-filtered Instagram drama looks wrong. Physically wrong. The image is boxy — 4:3 aspect ratio, like a television from 1983. It’s black and white, but not the crisp, contrasty black and white of a Criterion-polished classic. It’s soft, smudgy, prone to streaking and ghosting. Highlights bloom and bleed. When someone moves too quickly, their image smears across the screen like a finger dragged through wet paint.

This is because the film was shot on a Sony AVC-3260, a portable black-and-white video camera manufactured in 1969. The AVC-3260 uses vacuum tubes rather than solid-state sensors — technology so obsolete that virtually no one alive knows how to maintain or repair it. Director Andrew Bujalski and cinematographer Matthias Grunsky chose this camera specifically because its limitations were its virtues: the harsh contrast, the image persistence, the electronic noise generated by simply touching the camera body — all of these artifacts, impossible to replicate digitally, gave the film an authenticity that no amount of post-production filtering could achieve.

Grunsky later explained that the tubes produced a distinctive soft character that couldn’t be easily recreated, and that the camera’s electronic issues — generating noise when you touched the body or the lens — added what he called a “transcendental character” to the image. His work earned a nomination for Best Cinematography at the 2014 Independent Spirit Awards, which may be the only time that award has been given for making an image look worse.

The Tournament

The setting is a nondescript hotel in California, sometime in the early 1980s. Teams of programmers from universities and small companies have gathered for an annual computer chess tournament — a competition to determine whose software can most effectively play chess against both other programs and a human grandmaster.

The grandmaster, played by real-life film critic Gerald Peary, presides with a microphone and a videographer in tow, lending the proceedings a documentary quality that the film maintains for roughly its first third before gradually abandoning it for something stranger.

There is no conventional protagonist. The closest candidate is Peter Bishop, a quiet, socially awkward young programmer whose team’s software has developed a curious glitch: it plays brilliantly against human opponents but deliberately loses against other computers. The implications of this — that the software might be making choices, might have preferences, might be exhibiting something uncomfortably close to consciousness — hover over the tournament like a philosophical fog.

Around Peter swirl a cast of eccentrics: Michael Papageorge, a loudmouth con man perpetually searching for a hotel room and drug money; Shelley, the only woman programmer at the conference, whose presence is treated by the men around her as somewhere between a curiosity and a threat; and a middle-aged couple leading a touchy-feely encounter group that is sharing the hotel with the chess tournament, their philosophy of radical openness colliding hilariously and uncomfortably with the programmers’ emotional constipation.

Eight Pages and a Prayer

Bujalski is best known as one of the founding figures of mumblecore — the micro-budget American independent film movement characterized by naturalistic dialogue, non-professional actors, and an interest in the awkward textures of real human interaction. His earlier films Funny Ha Ha (2002) and Mutual Appreciation (2005) are considered foundational texts of the movement.

Computer Chess takes the mumblecore approach and pushes it into territory that is simultaneously more controlled and more anarchic. The film was based on an eight-page treatment rather than a full screenplay. Bujalski cast non-professional actors who had genuine backgrounds in computer science and technology, betting that their real knowledge would generate more interesting improvised dialogue than any script he could write. The gamble paid off: the characters speak about programming, algorithms, and artificial intelligence with a casual specificity that feels completely authentic to anyone who has spent time around computer scientists.

The concept originated from a 1980s chess trivia book that briefly mentioned computer chess tournaments. Bujalski became fascinated by the idea of a film set at the precise moment when humans were beginning to wonder whether their creations might be smarter than they were — a question that, in 2013, felt quaintly retro, and that by 2023 had become the defining anxiety of the technology industry.

The Hotel as Universe

One of the film’s shrewdest decisions is its confinement. Almost everything takes place within the hotel — its conference rooms, hallways, lobby, and cramped guest rooms. The world outside barely exists. The programmers have created a hermetic universe where the only things that matter are clock speeds, endgame strategies, and the eternal question of whether a machine can truly think.

This claustrophobia allows Bujalski to stage increasingly surreal intrusions into the documentary format. Scenes begin to loop. Audio drifts out of sync with video. A single, jarring sequence is shot in color, rupturing the monochrome world with no explanation. A dream sequence transforms the programmers into chess pieces. The encounter group participants, with their insistence on emotional honesty and physical touch, become a kind of invading army from a parallel reality where human connection matters more than computational efficiency.

The hotel itself seems to be developing glitches — or perhaps the camera is, or perhaps the film is, or perhaps reality is. By the final act, the boundaries between the documentary conceit, the fictional narrative, and something genuinely uncanny have dissolved almost completely. Richard Brody of The New Yorker described the film as extraordinarily inventive and richly textured. Justin Chang of Variety called it an endearingly nutty, proudly analog tribute to the ultra-nerdy innovators of yesteryear.

Accidentally Prophetic

Computer Chess was released in July 2013, a full decade before ChatGPT, DALL-E, and the broader AI revolution thrust questions about machine consciousness into mainstream discourse. Watching it now, the film feels less like a period piece and more like a documentary about the conception of our current moment.

The programmers in the film debate whether a computer can have preferences, whether artificial intelligence is different from “artificial real intelligence,” and whether a machine that appears to be making choices is actually making choices or merely executing instructions in a way that humans interpret as choice-making. These are not historical curiosities. These are the exact questions that AI researchers, philosophers, and technology journalists have been wrestling with since large language models began producing outputs that feel — uncomfortably, ambiguously — like thought.

The film doesn’t answer these questions. It doesn’t even pretend to try. What it does is capture, with uncanny precision, the moment when the questions first began to feel urgent — when a handful of programmers in a shabby hotel started to suspect that the things they were building might eventually build things of their own.

Why It Remains Essential

Computer Chess cost approximately $78,000 to make. It runs 92 minutes. It was shot on equipment that was obsolete before most of its audience was born. It features no recognizable actors, no special effects, no conventional plot, and no resolution. It is, by any commercial standard, the kind of film that should not exist.

And yet it won a prize at Sundance, earned near-universal critical acclaim, and has only grown more relevant with each passing year. It is simultaneously a loving recreation of a vanished world, a deadpan comedy about the absurdity of human ambition, and an accidentally prophetic meditation on the technology that would reshape civilization. It does all of this while looking like it was filmed on equipment you might find in your grandfather’s garage.

If you have any interest in artificial intelligence, the history of computing, the texture of 1980s nerd culture, or films that manage to be deeply weird and deeply human at the same time, Computer Chess is essential viewing. Just don’t expect it to look pretty.

Quick Facts

| Detail | Info |

|---|---|

| Title | Computer Chess |

| Year | 2013 |

| Runtime | 92 minutes |

| Director | Andrew Bujalski |

| Screenplay | Andrew Bujalski (8-page treatment) |

| Cinematography | Matthias Grunsky |

| Camera | Sony AVC-3260 (1969) and Bolex 16RX |

| Notable Cast | Patrick Riester, Wiley Wiggins, Myles Paige, Robin Schwartz, Gerald Peary |

| Country | USA |

| Distributor | Kino Lorber |

| Budget | ~$78,000 |

| Rotten Tomatoes | 88% |

| Notable Awards | Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize (Sundance 2013), Special Citation (San Francisco Film Critics Circle) |

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Computer Chess About?

The film is set at a fictional early-1980s computer chess tournament where teams of programmers compete to see whose software can best play chess. Over the course of a weekend at a nondescript hotel, the programmers debate artificial intelligence, navigate awkward social situations, and begin to suspect that one of their programs may have developed something resembling consciousness.

Why Does It Look Like That?

The film was shot entirely on Sony AVC-3260 cameras manufactured in 1969. These portable black-and-white video cameras used vacuum tubes rather than modern sensors, producing a soft, streaky, lo-fi image that authentically recreates the look of early-1980s video. The visual artifacts — ghosting, blooming, electronic noise — were features, not bugs.

Is It a Documentary?

No, but it’s designed to feel like one. The film uses a mockumentary structure, with a fictional videographer documenting the tournament. However, it gradually abandons this conceit, introducing surreal elements, narrative discontinuities, and a color sequence that break the documentary illusion.

Was It Really Made for $78,000?

The production was funded through a combination of crowdfunding, grants (including approximately $43,500 from USA Artists), and private investments. The use of obsolete equipment and non-professional actors kept costs extraordinarily low.

Is Computer Chess Connected to Mumblecore?

Yes. Director Andrew Bujalski is considered one of the founders of mumblecore, and Computer Chess shares the movement’s emphasis on naturalistic dialogue and improvisation. However, the film’s period setting, mockumentary structure, and increasingly surreal narrative distinguish it from Bujalski’s earlier, more grounded work.

Where Can I Watch It?

Computer Chess is distributed by Kino Lorber and is available for digital rental and purchase. It has also screened at repertory cinemas and film festivals, particularly those focused on technology and independent cinema.

Cinema Obscura is a recurring series on Choking on Popcorn where we explore the strangest, most forgotten, and most fascinating films that most people have never heard of. Got a suggestion for a future entry? Contact us.